Tatiana Chemi, Clive Holtham, Allan Owens and Anne Pässilä

Can a crisis act as a stimulus to change in higher education?

Historically, crisis can indeed stimulate educational change. Prussia had lost to Napoleon in 1807, their humiliation becoming embodied in the Treaty of Tilsit, so the efforts of Wilhelm von Humboldt from 1809-1810 to create the University of Berlin were rooted in a crisis of defeat not victory. Von Humboldt’s conception emphasised three unities, summarised by Pritchard:

- The unity of teachers and learners

- The unity of research and teaching

- The unity of knowledge

In 1972, initiated in the wake of les événements of 1968 and at a time when there were huge stresses across the world arising from the ends of empires on the one hand, and social tensions within Western societies in particular, UNESCO produced a global vision of education with four humanistic assumptions:

- Common destiny

- Democracy

- Complete fulfilment of humanity

- We should no longer assiduously acquire knowledge once and for all, but learn how to build up a continually evolving body of knowledge all through life—’learn to be’.

The aims of universities

We might summarise typical modern aims for universities as continuing the lineage of von Humboldt and UNESCO:

- Researching to develop new knowledge

- Teaching to help fulfil the potential of learners in secure, just, tolerant and sustainable democratic societies

In 2004, Manuel Castells addressed the roles of universities after receiving an honorary degree from City University, London:

I would say that there’s one major reason why universities as autonomous entities are essential – because the university is the last remaining space of freedom. There’s no other space in society, no other, that has not submitted to the power of bureaucracies or government or politics or to market forces.

Now we may decide that it’s okay, that we don’t need spaces of freedom and that market forces will take care of everything. But if we do think that we need this space of freedom it’s only the university that can provide it. No other institution guarantees it at this point.

While some might say this space of freedom has been widely eroded in many countries since 2004, for many this remains of profound significance. But that freedom is also burdensome. The university has to be prepared to be the critic of last resort.

Twentieth century crises – did universities get a pass mark as critics of last resort?

We have endured three massive and avoidable global crises in just 20 years:

2000: Financial crash with economic and social impacts

2007: Financial crash with economic and social impacts

2020: Health pandemic with economic and social impacts

In all three cases there were individuals and groups in universities who forecast the crises, and who developed ways to have avoided them, or reduced their impact. Some aspects of the crises, particularly the financial ones, were actually stimulated by methods engineered in universities. But the university sector as a whole clearly failed to act as the critic of last resort, especially after the 2000 crash when it was only a short time before a second version took place.

Universities cannot take all the blame, of course. The creation of the crises, and problematic responses to them, all represent profound and growing society wide deficits in wisdom, deficits which have grown considerably due to the speed of communication of mis-information in the internet era.

It would be difficult to argue that universities have failed in their everyday disciplinary research and teaching. There has been a massive growth in higher education. Huge advances have been made across all disciplines, within those disciplines, both in terms of the research and improving methods of teaching. So we are not being critical here of the everyday activities of universities. Our critique relates to how universities have addressed the big picture issues facing society, especially what became known as “wicked problems”. And in particular, we would argue that universities have lost sight of the importance of wisdom as opposed to knowledge and skills. Wisdom has been well understood for millennia. Practical wisdom (phronesis) was proposed by Aristotle in the Nicomachean Ethics, as one of the key categories of “intellectual virtues” alongside knowledge (episteme) and skills (techne).

The big difference from Aristotle’s time is that practical wisdom is now needed not simply by the elite, but by the population as a whole. The 1972 UNESCO report, points out, for example: “progress … in education and the spread of information, radically changes fundamental aspects of democratic practice”. And they conclude, “democratic education must become a preparation for the real exercise of democracy”.

While there have been admirable localised innovations to develop “preparation for the real exercise of democracy” in individual schools and institutions, the sector has a whole has sleepwalked through growing democratic deficits, despite having not simply the freedom that Castells identified, but also an implied duty to take advantage of that freedom. The continued challenges to “secure, just, tolerant and sustainable democratic societies” have been absent from the agendas of most institutions and most national groupings of institutions.

How the Humboldtian dream got lost

Humboldt advocated three unities, including the unities of knowledge. But the 19th Century saw two parallel developments that combined together to smother his dream. Firstly, commerce was driven by competition, in particular wherever possible to create monopolies through dominance. So businesses demanded excellence within individual disciplines and were ready to fund research within those disciplines. This was reinforced by nations competing with each other, and similarly funding disciplinary research to support war and infrastructure in particular.

Outside business, improvements in communications meant that the historic basis of professions, the guilds based in individual towns and cities, was steadily replaced by the creation of national professional bodies. By the end of the nineteenth century, both academia and professions had consolidated around discipline-based operations.

While Aristotle could embrace the whole gamut of science, management, arts and humanities, such a polymath would be nearly inconceivable today. Disciplines can and must solve many types of definable problem. But the most important problems in the world clearly cannot be reduced to solution by any single discipline. Certainly this has been true in the three big crises of 2000, 2007 and 2020, as well as the ongoing difficulties relating to climate change, regional conflict and income distribution.

Far from countering the dysfunctions of discipline-based research and education, universities in general have accentuated the discipline-based approach, not least in ranking individuals and institutions.

De-disciplining

There have been various attempts to counter the negative aspects of fragmentation of disciplines and knowledge, including developing polymathic or boundary-spanning individuals, or creating locales where different disciplines explicitly collaborate. Ideas of multi-disciplinary and inter-disciplinary approaches are appropriate for everyday problems, but remain too heavily rooted in the centrality of disciplines to address wicked problems.

Nicolescu has long advocated a more radical approach called transdiscipinarity: “that which is at once between the disciplines, across the different disciplines, and beyond all discipline.”

Nicolescu promoted the concept of indisciplinarity, building on its evolution in Art History as characterised by Thomas Mitchell who argues “indiscipline is a moment of breakage or rupture, when the continuity is broken and the practice comes into question.”

When it comes to addressing wicked problems, de-disciplining becomes essential, but over nearly two centuries both disciplines and their related professions have proved remarkably resistant even to modest multi-disciplinary initiatives, so those who advocate transdisciplinary and indisciplinary approaches face an uphill struggle. However, approaches that deploy arts to underpin transdiscipinarity are illustrated in Chemi and Xiangyun.

Learning for Practical Wisdom

We have created a framework for developing practical wisdom through education that has five dimensions, which we summarise below.

As was mentioned in the UNESCO report, universities focus on dealing with younger people at the beginning of their professional or academic careers. Aside from distance learning universities, there’s a lot less understanding in universities of how to deal with lifelong learning of adults. The mindset in higher education is almost entirely discipline-based. So as discussed above, to move towards indiscipline, is an uphill struggle.

The pedagogies in higher education are often transmissive in nature. Practical wisdom cannot be developed by sitting people in a classroom or online and teaching them in the conventional sense. It has to be some sort of active conversational learning, not least involving simulations of diverse types. Traditional university teaching is communicating relatively standardised content, while practical wisdom needs to be developed in a much more personalised and reflective approach. Finally, there is a visible hierarchy in most universities between teachers and students. Practical wisdom needs substantial peer-to-peer learning, what Illich called a “web” long before the internet had spread internationally, and nearly two decades ahead of the world wide web.

These five dimensions run against the grain of the modern university, embedded in their operational, everyday assumptions of how to run typical higher-education institutions. The final column assesses whether the COVID-19 crisis has helped. We feel that the shift to fully online learning has introduced many academics to a world of distance learning with which they were wholly unfamiliar. At least some have realised that learning at a distance, the only method that can address the practical wisdom gap for adults en masse, need not be a second-class experience. So there are overall some slight positives in the current situation, but unfortunately they don’t outweigh the resistance that will come from difficulties in unlearning the status quo.

Something can be done: case study

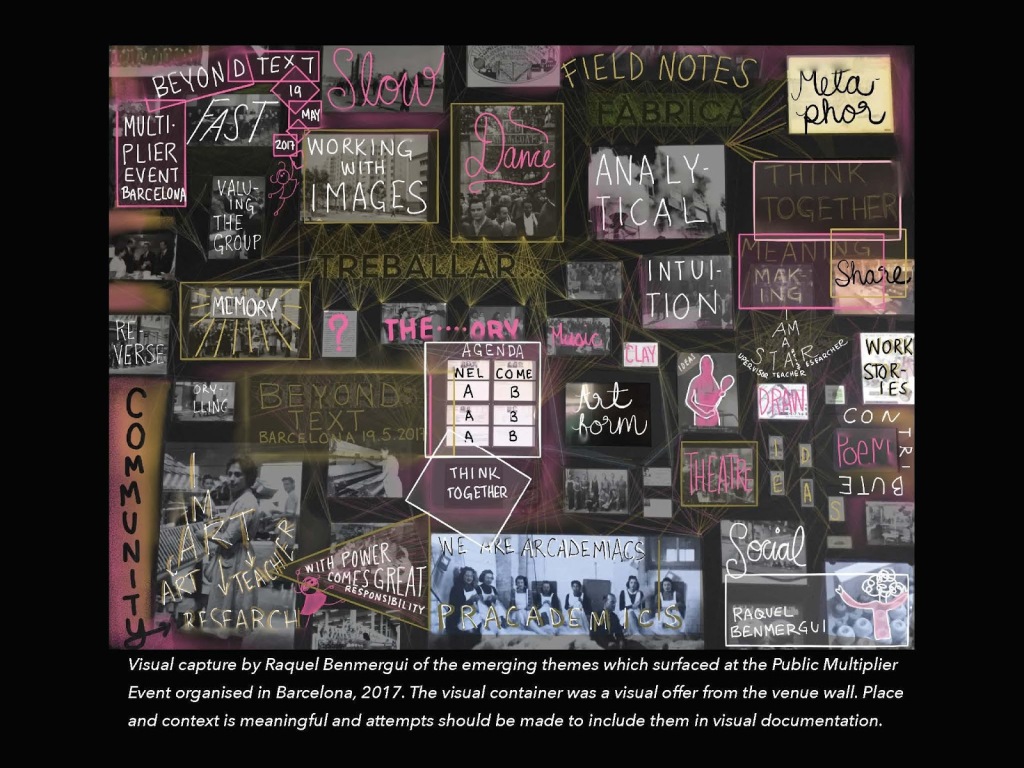

One way of making progress on significant change is through prototyping alternatives, and it is perhaps not surprising that we report here on an EU Erasmus funded project, since EU initiatives tend more explicitly to address UNESCO-type assumptions than do similar UK programmes. The Beyond Text project (2016-2019) formally related to arts-based methods for research, assessment and evaluation, but ultimately turned out to be about creating an indisciplinary community of adult learners, able to test and demonstrate a wide variety of methods for developing and articulating practical wisdom in a democratic fashion. The e-book which summarises the project demonstrates how art-based methods can challenge more traditional publication methods. The table summarises how far it addresses the practical wisdom learning framework.

Overall, as Bobadilla et al envisaged, such an arts-based approach “opens up the possibility for asserting counter-discourses that promote alternative frameworks and create possibilities for critical resistance”.

Conclusion

In helping society address its most profound and wicked problems, universities need to augment their traditional delivery of research and education, through an additional focus on developing practical wisdom in adults. In crime dramas, the detective looks for means, motive and opportunity. We believe that that the university sector almost literally is the only sector that has the means to do this.

The real problem area is motive. Universities are so preoccupied with their success on conventional metrics relating to everyday and familiar discipline-based research and education, that they may be extraordinarily reluctant to commit to indisciplinary activity. Sadly we fear that disciplinary mindset will hinder not just pursuit of solutions to wicked problems, but even the pursuit of democratic societal goals of safety, justice, tolerance and sustainability.

COVID-19 presents a dramatic opportunity, and has certainly helped unfreeze some previously held views on large scale learning for adults, and awareness of appropriate pedagogies for that.

Photo by Elena Mozhvilo on UnsplashCopy

Tatiana Chemi, PhD is Associate Professor, at the Department of Culture and Learning at Aalborg University, Denmark. At the Chair of Educational Innovation, she works in the field of artistic learning and creative processes.

Clive Holtham is Professor of Information Management at the Business School, City, University of London and a National Teaching Fellow. He is Director of the Learning Laboratory, whose innovations include the award-winning learning by wandering around (dérive). He co-founded the Centre for Creativity for Professional Practice at City, which led to the unique transdisciplinary Masters in Innovation, Creativity and Leadership.

Allan Owens is Professor Emeritus of Drama Education, RECAP, University of Chester and a National Teaching Fellow. His current research interests include learning through arts-based research practices and other critically creative pedagogies both within and beyond the academy.

Anne Pässilä, (PhD) is Visiting Research Fellow at RECAP and Senior Researcher at LUT University, Finland. She specialises in applying arts-based initiatives and arts pedagogy to support innovation and development processes in the public, private and third sectors.